So Many Perched and Resting Swainson's Hawks

These birds have begun their very long migration

Swainson's Hawks are very interesting raptors for a few reasons. First, many of them migrate an incredible distance twice annually from their breeding grounds in the western states to their wintering grounds in Argentina. And second, they come in a range of plumages. The birds I just saw on a farm in Pima County were among a group of well over one hundred that have begun their fall migration south. They stopped at this farm to rest and to feed.

Compare the plumage of the bird above to the bird below, and then compare those to all of the subsequent images in this post. You will see a variety of colors. Some, like the Juvenile and sub-adult (immature) Swainson's hawk below, will have dark streaking down their breast along with a pale head.

Swainson's Hawks favor open grassland and prairies but they have adapted well to agricultural areas. This farm had freshly cut alfalfa lining some fields with bales of hay. The farm also had other alfalfa fields flooded with water. All of this area offered potential for great prey for these birds.

Generally happy with the three "R's" of a typical raptor diet (rodents, rabbits, and reptiles), Swainson's Hawks dine on insects including mainly grasshoppers during the non-breeding season and while they are migrating south. Swainson's in migration make short hops as they travel, taking their time on their way to their destination. At each stop along the way, they spend time feeding and building fat stores for the next leg of their journey.

Swainson's Hawks are similar in length to Red-tailed Hawks but are a bit lighter and more slender looking. What are all of these birds doing here in Pima County? Birdnote has the answer.

The Swainson's below is what is called a dark morph. The front of the bird is a dark brown. Most of the Swainson's we see are a lighter morph (a variation of plumage) but dark morphs are not uncommon. By the way, the yellow 'spots' in the field are some of the many Orange Sulfur butterflies that were present. Commonly known as "Alfalfa Butterflies", the larvae (caterpillars) of the Orange Sulfur primarily feed on alfalfa plants. Alfalfa is considered a "host plant" for these butterflies.

Next you can see a more typically patterned Swainson's Hawk. It has a distinct bib on its chest, and then a lightly colored belly. The afternoon we were observing these birds was very hot, with the temperature well above 100°. The hawk had its wings spread to dissipate heat and was breathing with an open mouth- another method for giving off heat.

Typical of many area farms, there is a row of primarily mesquite trees on two sides of the farm. Some of the Swainson's chose those spots to perch. Sometimes the hawks were in the trees but were not where we could get a clean look at them. Often they would take off flying if our truck rode down the farm road adjacent to the trees.

We were grateful for the Swainson's that perched out in the open and grateful for the ones too tired at the end of the day to fly off immediately..

Yet another immature Swainson's, breathing with an open mouth, at the end of a very hot day.

This is another immature dark morph Swainson's Hawk. It is much darker than the bird above. It also has one feather out of place

Here is the same Swainson's Hawk just moments later. You can still see the feather on its side that is ready to fall off. Now the bird is trying to cool down from the heat. Its wings are spread and its bill is open. For me, the highlight of this shot is the bird's eye. That light blue glassy look is due to the bird's nictitating membrane. Birds have a third 'eyelid' that is translucent. It serves to protect the eye and helps to moisten the eye, all while allowing the bird to see through it. I just happened to take the photo when the hawk was engaging its nictitating membrane.

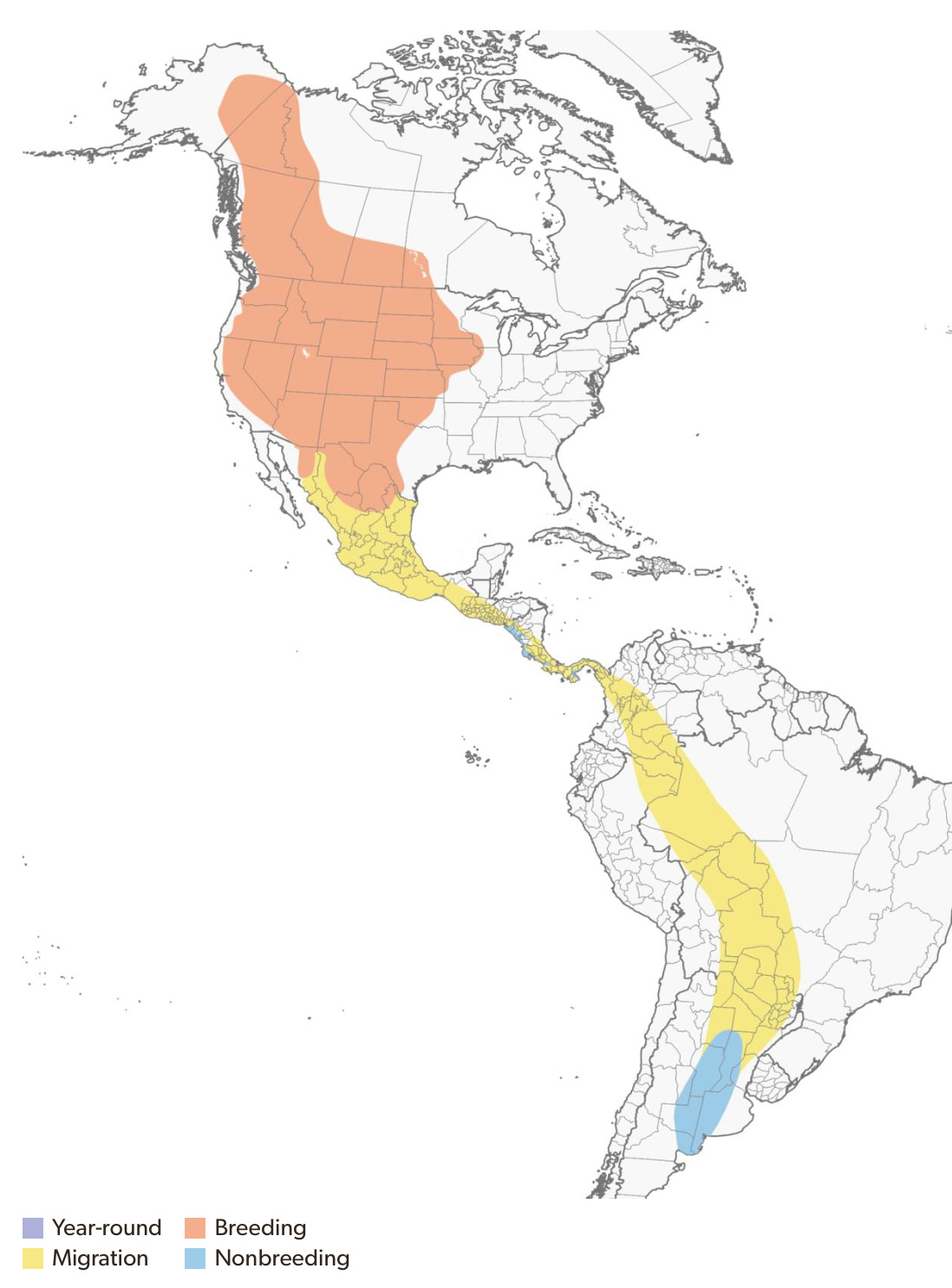

Next up, Swainson's Hawks in the air. The range map below from AllAboutBirds shows the incredible round-trip flight that this species makes every year.

Most of the world's estimated 900,000 Swainson's Hawks make this round-trip flight of up to 12,000 miles every year. Current population declines are due to loss of prey and nesting sites. The loss of pastureland and the consolidation of small farms into larger agribusiness have also had a negative impact on Swainson's hawks.

It seems to be at least 3 or 4 weeks ahead of schedule this year. I wonder if that's a consequence of climate change?

They are racking up the frequent flyer miles!